A Great Success Story? Be Careful of Paying a High Price

Forecasting Growth Rates

By:April 14, 2023

Ready to Enhance Your Investing Skills?

Get free essential insights to advance your investment journey.

Access the Quickstart PDFIf we think about analyzing stocks at the most basic level, everything we do boils down to answering three questions. They are: “How much money will the stock earn?,” “When will that happen?” and “What are we willing to pay?”

No problem, we say to ourselves, at least at first. But then we start thinking about how uncertain the future really is.

Consider new car sales. Car demand disappeared during the pandemic, but now autos are routinely selling at list price or even at premiums. Will that continue? With so many workers continuing to work from home, will there be less demand for cars? Will auto sales decline?

How about gas prices? If you’re not into investing into auto manufacturers, what about pharmaceutical companies? Their profits are tied to possible blockbuster drugs that often fizzle before making it to market.

Even stocks that are so-called “sure things” really aren’t. Before there was Facebook, Apple, Amazon Netflix and Google, there was America Online, AT&T, IBM and General Electric. Those stocks were believed by many to be sure things. In the 1960s and 1970s, there was a list of blue chip growth stocks called the “Nifty Fifty” that were pitched as “buy until you die.”

Nifty Fifty examples include Digital Equipment Corporation, S.S. Kresge (the parent of Kmart), Polaroid, Eastman Kodak and Xerox. Though many of those companies survive today or have successfully merged with other companies, quite a few have languished or gone bankrupt as well. The lesson here is that nothing lasts forever, nor is anything guaranteed.

How Growth Rates Affect Stock Values

There’s a formula analysts use to estimate the “true” value of a share of stock. It discounts the projected future cash flows according to risks and what an investor could get in a risk-free investment.

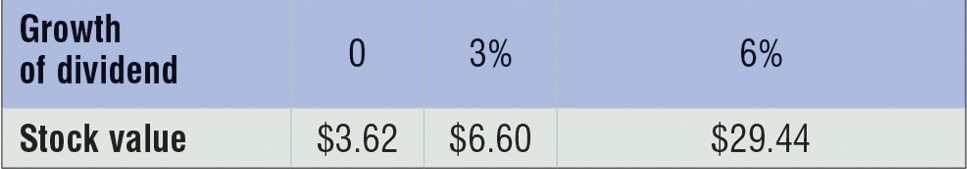

Rather than bury readers in math, here’s an example of what a stock with average risk would be worth if it were paying 25 cents in dividends (see table). For you finance majors, we’re using a single stage dividend discount model with a CAPM (capital asset pricing model) derived discount rate when the 10-year Treasury is at 1.3%, beta is 1 and the market risk premium is 5.5%, leading to a 6.9% discount rate.

You don’t need to be a finance major to look at that table to see the impact of different growth rates on stock values. You can imagine why any news related to the outlook for a company’s long-term profitability has a big effect on the stock price.

What You Need to Know About Forecasting Growth

Truth is, nailing a company’s growth rate is mighty difficult, so we do the best we can and accept we’ll often be wrong. Investors often start with the Street’s average forecast and nudge it up or down according to whetherthey feel more optimistic or pessimistic than other investors. Unfortunately, that ignores studies that indicate Wall Street estimates are notoriously optimistic.

You might do better erring on the conservative side of any nudging. Small misses on near-term earnings forecasts usually don’t have a large impact on stock valuations. There might be a short-term blip as the market digests the news. If that miss is tied to a potentially longer-term phenomenon, then it can have a larger impact when the market lowers its long-term estimates.

The biggest mistake you can make can come assuming a phenomenal growth rate will continue indefinitely. Companies face competition and consumers’ tastes change. Regulators may decide a company is engaging in

monopolistic practices or simply seek to reduce its power, as we’re seeing with Google and Facebook today. Executives can make mistakes. Firms can certainly grow profits at rates of 10% or 20%, but not forever.

Another reason to avoid forecasting that astronomical perpetual growth rate is the limit imposed by how quickly an economy can grow. The United States’ gross domestic product, a broad measure of economic activity, has grown at a rate of less than 2% in the post-WWII era. Given enough time, a company growing at a rate substantially faster than the U.S. economy would be larger than the total economy. That’s paradoxical.

Rapid growth is allowed, but only for a finite amount of time. Analysts have a few tools in their kit to account for periods of high growth. They might divide growth into two or even several stages. At first, a company might grow at an unusually high rate and then taper off or even begin to decline.

Most of us don’t want to bother with those formulas, nor is it usually worth the additional trouble because, again, it’s unlikely we’ll be spot on anyway. But what we can do is be very cautious before we believe a company can grow at astronomical rates forever. We must be wary of paying exorbitantly high prices for good growth stories, because that means the Street has bought into those imaginary growth rates. We know better.

This article was originally published in the October 2021 issue of BetterInvesting Magazine.